At last week’s Science Communication Conference, I joined a plenary panel to discuss what’s changed in the 12 years the conference has been running. I’ve been kicking around in the sector for more like 25 years so I played a bit fast and loose with the timescale, but my little spot in the limelight went more-or-less as follows:

Tag Archives: featured

Is Mirobot the droid we’ve been looking for?

In the previous post I wrote about the challenge of catching and holding peoples’ attention with electronics and programming activities – if you’ve seen DEMO: The Movie you’ll know I’m quite big on attention.

The Arduino microcontroller platform is a terrific tool, but it’s hard to present a project which is both immediately appealing and instructive. Projects tend to be fun but complex, or useful-but-dry tutorials. As with many fields of life, I suspect the answer is: robots.

Frikkin’ robots.

Lots of robots.

Continue reading Is Mirobot the droid we’ve been looking for?

Domino Computer

Stand-up mathematician Matt Parker and a team of volunteers build a functioning calculator out of dominoes, because… er… well, because they worked out how they could.

This has been festering in my pile of ‘unfinished hobby projects’ for longer than I’d care to admit, but just before I gadded off on holiday last month Matt prodded me with a very pointy stick. I’m delighted the film is finally seeing the light of day.

The film follows the domino computer build weekend at Manchester Science Festival with all its up and downs, and while we did try to explain how it works… well, turns out that’s quite tricky with hundreds of people milling around and thousands of dominos ready to fall over at a moment’s notice. So you might also want to check out this Numberphile film in which Matt explains the circuit with a little more care:

The team have also put together some worksheets, and can provide schools’ workshops (and dominoes!): think-maths.co.uk.

Elin also has a great bunch of stills of the weekend over on Flickr. Here’s one now. Note the breaks in the circuit during building, so an accidental fall doesn’t destroy the whole thing. There was a heap of work and expertise involved in building this thing, it really was a remarkable effort.

The dotted line

Occasionally I’m drawn in to youtube via links and twists so convoluted that I can no longer remember where I began. That’s how I came across this delightful video of M.I.T.’s Walter Lewin this week:

It’s interesting to see discussions around Lewin and pseudoteaching, but that doesn’t deny his high production values here. Every lecture was, he claims, rehearsed at least three times in full before his first audience was brought in. Clearly, when he decides to do something, he is interested in mastering the art. Even if that art, at first glance, appears mundane.

There are many things that we do that could be tweaked and improved. All we need to do is look at ourselves from the outside occasionally and see what else we can give. If we do something many times during the day, in front of an audience, we may as well learn to do it with finesse. If we’re on a stage, we should deserve it.

Seeing that drawing a dotted line can help make us engaging, memorable and inspirational, perhaps like me, you too want to draw dotted lines like Walter Lewin. You’re in luck.

Or perhaps you’d just like to rock your syncopated head to his dubstep. You can do that too.

Of course you can. The internet is like that.

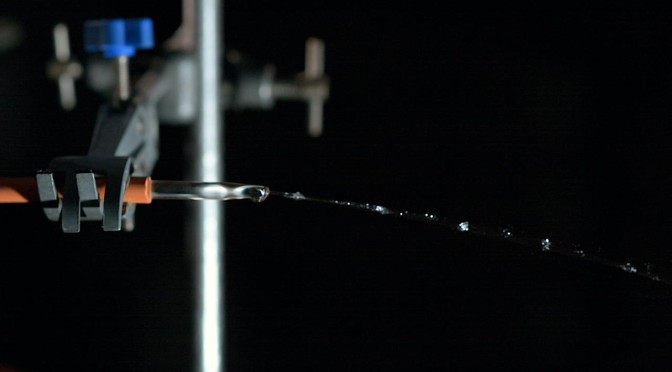

Pearls in Air / Pearls of Water

This is an example of a demonstration where video doesn’t come close to capturing the awesomeness of seeing it for real. I love seeing students have the same reaction to it as I did when I first saw it – one of joyful wonder at seeing something which appears to defy the laws of physics, of seeing something impossible.

Pearls in air can be a tricky demonstration to set up and I have to confess that, until making this film, I’d never had to set it up myself as I’ve always worked in schools where the physics technician did it for me. The version shown in the video isn’t perfect – it’s possible to get a better looking stream of “pearls”, but I’m OK with that because it’s honest in its depiction of what can be achieved in a limited amount of time with limited resources.

I find this demo incredibly useful for teaching about projectile motion and it’s a nice companion to the monkey and hunter demo which I think was the first demo film Jonathan and I made together.

This film was produced for the Get Set Demonstrate project. Click through for teaching notes, and take the pledge to perform a demonstration to your students on Demo Day, 20th March 2014.

This film was produced for the Get Set Demonstrate project. Click through for teaching notes, and take the pledge to perform a demonstration to your students on Demo Day, 20th March 2014.

Flame colours

A scary article in the NY Times last Friday about a chemistry demo they refer to as “the rainbow”:

“With about 30 students watching from their desks, a snakelike flame tore through the air, missing the students closest to the teacher’s desk, but enveloping Alonzo Yanes, 16, searing and melting the skin on his face and body, according to witnesses. He was in critical condition on Friday[…]”

Just weeks ago, the article relates, the demo was the focus of a safety bulletin from the US Chemical Safety Board, and this film:

Here in the UK, I think we’d more commonly refer to the demo as “Flame colours”, and at the head of this post is a photo I took of it a few years ago. As best I can tell, the cause of the accidents in the US has been demonstrators topping up the flame straight from the methanol bottle, leading to the ignition of a large volume of fuel vapour.

Now, I’d hope most people reading this blog will be wincing right now. It was drilled into us (in school) that you never open a bottle of fuel near a naked flame, and that the correct procedure here is to ensure the watch glasses are cold before adding a small amount of fuel (typically with a pipette), then sealing the fuel bottle and removing it to a safe distance, before lighting the mixture in the watch glasses.

That would be standard lab practice, and it’s near-inconceivable that a teacher would pour meths from a bottle directly onto a flame. However, one thing we learned from SciCast is that we’re into the second generation of science teachers who’ve never really ‘done’ practical science. Recent science graduates don’t necessarily know how to handle flammable materials; they may never have been taught.

That generational knowledge gap was one impetus behind the demonstration films Alom and I have been making for the National STEM Centre and others, and also for this website. So pass this on, please, and let’s not make assumptions.

Oh, and if you’re a teacher in the UK, the version of this demo you should do is probably the one with ethanol spray bottles. That’s the version the Royal Society of Chemistry and Nuffield promote, but – as ever – check with CLEAPSS for their standing advice.

[EDIT 9/1/2014 – The RSC’s Education in Chemistry blog has picked up the story. Their post includes a quote from Steve Jones, Director of CLEAPSS.]

[EDIT 2 15/1/2014 – I somehow missed the NY Times’ follow-up story about the school involved in the incident above being inspected by the Fire Department, and being given notices to improve on a range of issues. Also, for the UK audience I should note that the Scottish equivalent of CLEAPSS is SSERC.]

Sharing science through story

Former FameLabber Feargus McAuliffe speaks at TEDxDublin about how he to learned to share science by telling stories about it.

It’s an interesting watch, but I’d go much further than Feargus: I think the peculiarity is the formalised ‘present your evidence’ model of science, and that in the general case, all communication is storytelling. Indeed, it’s mostly scientists who baulk at that idea – for people in the media and comms worlds, their surprise is that this is even a discussion.

One of the reasons I believe demonstrations are valuable is that they present ideas from science in a (usually very simplified) narrative structure. You begin with an arrangement of apparatus; something happens; the state of the apparatus has changed.

Demos are stories.